During a drought, visceral leishmaniasis spreads, testing a small rural hospital in Ethiopia

This is the story of the regional response to contain the surge

Visceral leishmaniasis is a parasite, spread from sand flies that live near termite mounds.

It invades the blood system, attacking every organ in its path. It leads to death in 95% of patients who show symptoms, if it goes untreated.

"If no one stepped in, a lot of people would've just died in their house. At the end of the day, all of the patients we treated would be dead if there was no response from anyone," Dr. Kebron said starkly.

“It hurts,” Berkede complains as his nurse injects him with medicine to treat visceral leishmaniasis, a deadly parasite spreading in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley. He squirms, clenching his fists, and moving his head from side to side.

Berkede is a tall, lanky boy who’s been in the clinic for more than a week receiving treatment for visceral leishmaniasis. At 15 years old, he is responsible for looking after his family's cattle. He laughs when asked how many cattle he watches over. “A lot,” he responds.

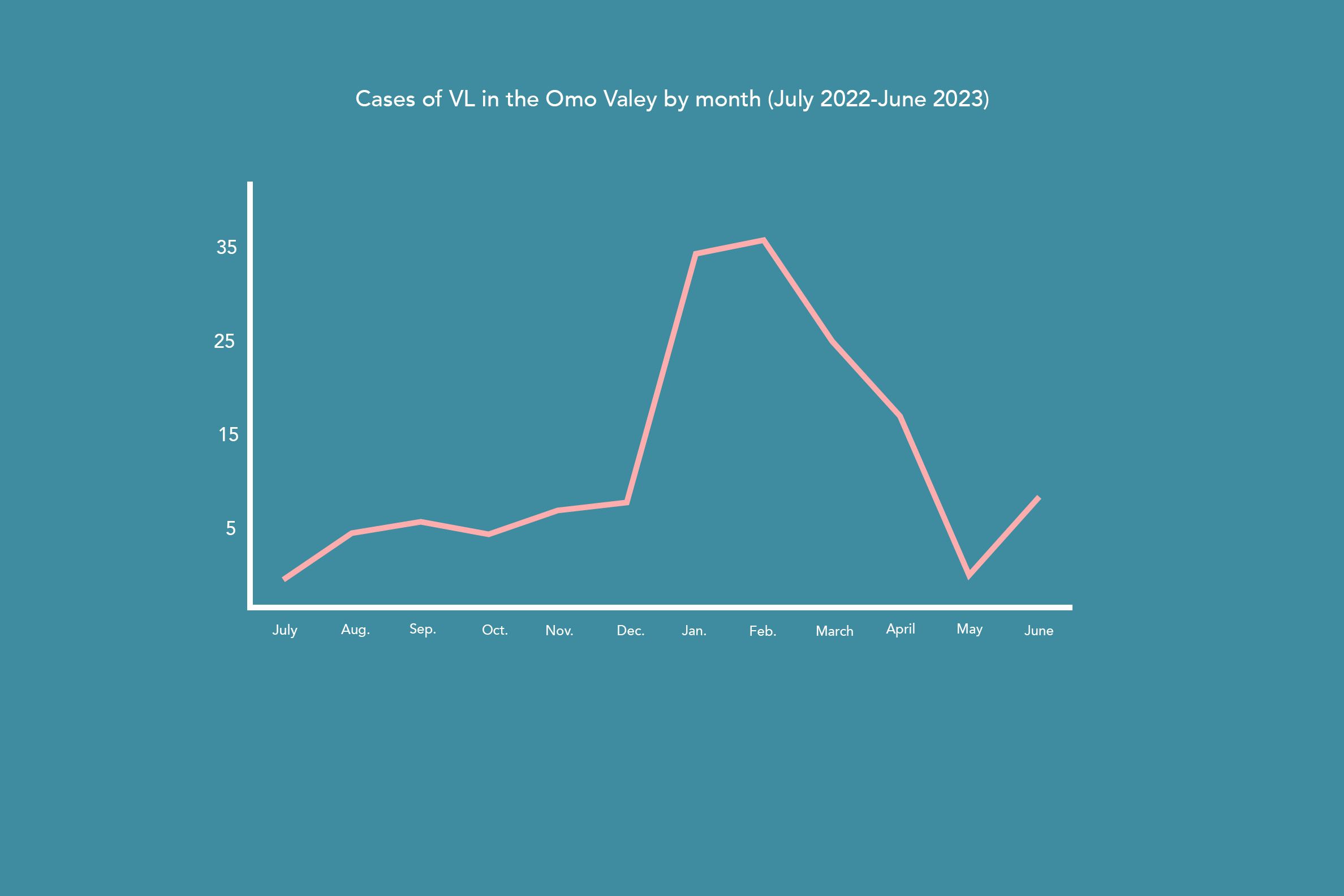

His nurse Ali Mohammed, 25, is a small man with a giant smile. Berkede towers over him when standing. His smile is in contrast to the seriousness of the work he is undertaking. He starts his rounds treating patients each day at 10 a.m. Berkede is his first today. At the beginning of April, Ali had nine patients for VL, but in January the small clinic was filled with more than 25 people, many in critical condition.

The clinic is a small standalone building at the Jinka hospital converted from a COVID-19 ward. It is one big room with single beds lining the sides. The windows are open to let in fresh air, but it can still feel stifling hot inside.

VL is a parasite that invades the blood, attacking every organ in its path. It causes fevers, fatigue, and uncontrollable bleeding, and it destroys the immune system. If left untreated, nearly every one who starts to show symptoms of VL will die. Patients mostly succumb from other diseases like infections and pneumonia because the parasite destroys the patient’s immune system that would normally respond to these diseases.

As Ali moves on to the next drug in the dose, Berkede continues to move around uncomfortably. The medicine is the only treatment available for VL in this hospital, but it is a muscle irritant and extremely painful. At minimum, a patient needs to take this drug for 17 straight days, and there are patients as young as 4 years old.

In his normal life, Berkede is strong, tasked with walking around following the cattle as they find pastures to graze for hours each day. As he sits in the hospital, he is worried about his cattle and how his family is coping without him. But VL causes intense fatigue, which means he has spent most of his time here, laying in his bed, trying to regain his energy.

On the Edge

A short film inside the rapid response to contain a surge of VL cases in the South Omo Valley, Ethiopia

Visceral Leishmaniasis spreads in the Omo Valley

In a normal year, the South Omo Valley might see 10 cases of visceral leishmaniasis. It spreads by the bite of a sand fly that lives in giant termite mounds. When a person has VL and is bitten by the sand fly, the sand fly can then spread it to another person by biting them.

However, the area has been experiencing severe drought for the last 6 years, causing massive food insecurity and creating a ripple effect for VL. For the last five years, the rainy season has produced below average amounts of rain, which is causing cattle to die. Humanitarian agencies have described it as one of the worst food shortages in decades in the area, and scientists agree that the drought is a direct result of climate change.

A strong immune system can fight off the parasite, but if a person has an immune suppressing co-morbidity, like malnourishment, it is much harder to stop the parasite. On top of this, because of food insecurity many groups are moving around in search of pastures for their cattle, which is causing people with VL to go to areas where it wasn't previously present, creating a nightmare scenario.

“So far, 22 patients have died, but 200 patients would have died if there was no response from the ministry,” Dr. Kebron Haile, Technical Advisor for VL, the END Fund, declared, mostly because of a lack of blood supply. VL patients require many blood transfusions and subsequently deplete the local supply when there is a surge. These shortages are not contained to VL patients and can cause additional problems in care for other people who also require blood transfusions like mothers giving birth.

Join us in responding to VL in Ethiopia

Cases of VL in the Omo Valley by month

(July 2022-June 2023)

However, this number only represents a fraction of the overall cases in the area, as most never make it to the health clinic. “We have heard rumors of around 70 people who died in their villages,” Dr. Kebron continued, “and we think there could be 300 or 400 more undiagnosed cases.” This poses an overwhelming problem because not only are those people at risk of dying from the disease, but they continue to spread it to others.

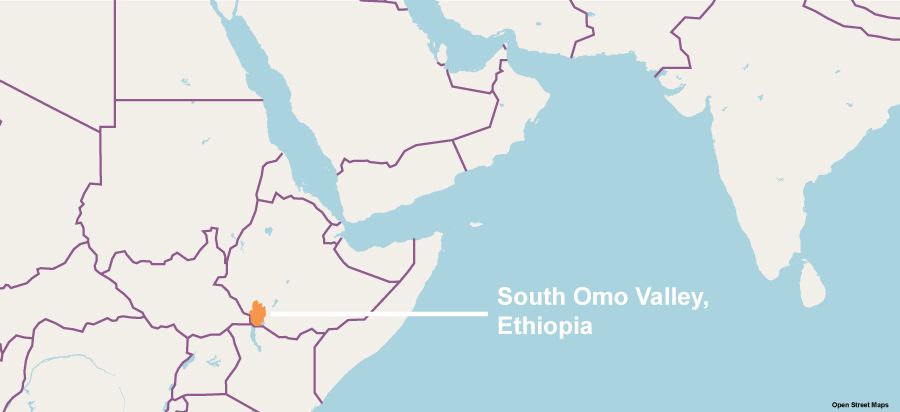

The South Omo Valley is roughly the size of Maryland, located in South West Ethiopia and shares a border with Northern Kenya. A little more than 750,000 people live there, making up more than 12 ethnic groups, each with their own language. One of its smallest groups, the Mursi tribe, only has about 12,000 people and its own language.

Paved roads connect the different small towns until suddenly they stop and force cars onto rough dirt roads. For many people who live off of the main road, cars can't reach them. The sheer distance between population centers makes it difficult to respond, as community health extension workers are trained to identify the symptoms of VL and refer them to the one hospital in the area that has the medication to treat the patients.

To find cases, the region relies on health extension workers, a type of liaison between communities and health systems. The health extension workers are paid a small amount and are expected to travel from house to house inquiring about the general wellbeing of residents. Houses can be anywhere from a short motorcycle trip away, to more than a six hour round trip on foot. They’ve recently been trained to look out for the signs of VL and if communities are in a clustered area, they provide information about how to prevent the disease, like avoiding areas where the sand fly breeds.

Tefera Mesele, a dedicated health extension working in the area, is a tall man. As he walks up to homes, he towers over the families living there, but he gets a warm response. Each family living here knows him because he lives close by and routinely walks around to check on them. As he takes a seat, the family gathers around to listen and answer his questions about noticing anyone with VL. If someone is showing the symptoms, he will take down their information and call a regional disease surveillance officer, who will then be sent out with a rapid testing kit known as the rK39. The kits are in short supply, so it is paramount that the health extension workers find probable cases.

Tefera Mesele, a community health extension work in Ethiopia, speaks with a gathered family about visceral leishmaniasis

Tefera Mesele, a community health extension work in Ethiopia, speaks with a gathered family about visceral leishmaniasis

At this point, if the test is positive, they need to find transportation to the Jinka hospital, the closest facility with the medication to treat the disease. For some like Berkede, it will mean traveling in the back of an ambulance for four to five hours.

Quickly getting to the hospital is vital for increased chances of survival, according to Dr. Abraham, Director of the inpatient ward at the Jinka Hospital. “When they visit us, most patients are in terrible condition. A patient’s chance of survival will be diminished if he or she arrives at our hospital after becoming ill.”

The effects of VL cause a ripple in the entire health system. Since VL is so intensive to care for, it eats into the regional health system’s response for other diseases. A VL patient could need many liters of blood, draining the local blood reserve. A patient will be in the hospital, potentially in a critical state, for roughly three weeks, requiring around-the-clock care. 200 humans infected with VL means that the local health system needs to prioritize resources away from other needs to provide care for them.

“The treatment of other diseases would be impacted if we do not address the leishmaniasis…since the VL ward opened, there is a worsening medication shortage,” Dr. Abraham explained.

In a place like Jinka, where the sole hospital for the region only has 340 total staff members, including support personnel, a surge of VL cases can severely disrupt the normal operations of the regional health system.

The sandflies live in giant termite mounds that litter the landscape.

Often people come in contact with the flies while looking after their grazing cattle.

The response:

VL is unlike many of the diseases that garner international attention. Its threat is local and extremely remote, and it doesn’t have the ability to spread around the globe. There isn’t an easy intervention like a vaccine to make for a quick win, and it affects those on the margins of society.

"These are actual human beings that are dying, actual families that have been affected by this disease," implored Dr. Kebron.

However, the answers are known. With more resources, the ministry of health can hire more disease surveillance officers, procure more tests, buy larger quantities of drugs, and set up clinics closer to communities in need. Curtailing the surge early ensures that it doesn't spread uncontrollably.

The response has already seen improvements in the situation. Less people are coming to the clinics and importantly those that are coming are less sick, which means that their chances of recovering are greatly increased.

“As soon as I started to take the medicine, the pain and fatigue began to go away,” Berkede declared with a smile.

Learn more